Leaving it all Behind

The afternoon had arrived. I hadn’t thought too much about this moment. I’d thought lots about being uncomfortable, about being lonely and, since receiving a message from a friend in back home the day prior, about being hungry. But, generally, it was safe to say I didn’t know what to expect. I had just eaten a monster lunch and kissed my wife goodbye and now it was time to join the queue.

Years of Anticipation

I’d first heard of Vipassana meditation six and a half years earlier. Over a serving of Gobi Manchurian in a beachside shack in a hippie enclave of northern Goa, I’d struck up a conversation with a South African sailor who had recently completed the ten-day silent course. I, to this day, can’t put my finger to what resonated so deeply, but I do remember exiting that interaction thinking: “Hmmmm, I’ll probably do that one day”.

Years passed and, with the exception of a few email enquiries I’d sent out to a course centre in rural British Columbia shortly after returning home from that trip, my intention to subject myself to a week and half of sitting in silence had laid dormant. Well, up until 60 days before this moment that is.

Now, in the fall of 2019, I saw a sliver of opportunity. My wife and I had just arrived in India. We had spent the last five months cycling from Georgia through several former Soviet republics, western China and Pakistan. As we neared India, the end point of our cycle trip, we shifted our gaze momentarily up from the potholes and dreamt about how we might spend our time in the Subcontinent. For me, I quickly thought to a Vipassana meditation course. If I couldn’t motivate myself to dedicate ten days to seeking enlightenment while on an eleventh month adventure with plenty of unscheduled time, then I probably wasn’t ever going to make time to do so.

I researched my options and quickly settled on applying to join a course in Dharmasala that was scheduled to commence two months hence. What was my criteria you ask?

- Somewhere not too hot.

- Somewhere my wife would be safe and have fun while I was in meditation jail.

- The adopted home of the Dalai Lama seemed like it must have some good karma going for it.

It took a few weeks, but soon my application was accepted and I was granted a spot in the course. After escaping China, riding most of the Karakoram highway, trekking to the lap of the mountain Gods and celebrating our safe arrival in the world’s most populous democracy, I was set to embark on a new challenge, alone. And, similar to our last one, minimally prepared.

Down to Dhamma

A cluster of people congregated around the two tables. Volunteers processing our paperwork sat opposite. Each participant was in a varied state of distress and on show was a comical microcosm of humanity. Each of us battling various personal philosophies, engrained cultural practices and an awareness that we were all on the cusp of diving head-first into a possibly transformative experience. There was nothing but silence and solitude to rush towards, but still people jockeyed for position to be admitted to the centre ahead of others. It was ironic agitation for a cohort of individuals who were about to embark on a quest to ignore craving and achieve equanimity.

Eventually, with my dirty laundry sack clasped in my left hand and a tag marked “A-4” that indicated my room allocation in my right, I walked through the gate. Once the rest of the male students had passed through, this gate would close behind us. With the bounce of a self-righteous student who had re-read the school rules before his first day, I bypassed the valuables check-in. I had left the long list of forbidden items – phones, computers, writing utensils and books – with my wife. Assuming you don’t count a dose of apprehension, I had brought little more than a bundle of warm clothes and my toothbrush.

My cavern-like cell surpassed my modest dreams. I was grateful. I would, at night, have at least one wall buffering me from the constant chorus of burping, farting, snoring and coughs that, within hours, would form much of the auditory segment of my daily experience in the Dhamma Hall.

It was only 3 pm. There were four hours until we were expected to assemble in the dining hall to be welcomed, read the riot act and, most momentously, begin our noble silence.

Noble silence you wonder?

Yes, noble silence. Sounds great, right?

Noble silence means no communication – no speaking and no eye contact, no writing and no reading. From 7 pm on this day until approximately 10:30 am on the 10th day, every participant was to observe noble silence.

Well we had a few hours to kill before the clock turned 7. So…

…I ran away.

A Last Last meal

There was a chai shop located outside the entrance of the mediation centre. Clutching at the last vestiges of freedom, I ordered a cup of sweet, milky chai and sat. Upon seeing another patron order an aloo paratha (India potato pancake), I too, despite still being full of my monster lunch, ordered a paratha. I regretted not having a book or a journal with me. No matter. I am strong I told myself. I am about to be constructively alone for 10 days. What’s a few extra hours?

Suddenly, a middle-aged foreigner, looking slightly distraught, turned the corner into the chai shop and, to no one in particular, asked: “does anyone know where I can get a towel?” The flock of young locals searing parathas behind the counter didn’t offer a response. I suggested she ask at a guesthouse nearby. “Could be a good karma boost,” I smirked to myself.

Once I was no longer enjoying my charade of final freedom, I wound my way slowly up the steps to the meditation centre. I was now in for good.

Some men were milling around in the courtyard. Most were chatting and laughing near the dining hall. I poured a cup of water and sat. I floated in and out of conversations. On one hand it felt odd to again be around Westerners. There hadn’t exactly been lots in Pakistan and Xinjiang. On the other hand, I had already committed to winding down my brain activity and, without too much care for others, I limited my involvement to listening.

I was jolted by one guy however, a young bearded dude from Delhi who I would come to refer to (only in my own mind of course) as “Cowboy”. Without introduction he demanded to know how I had succeeded in registering for this course. Uncertain of his angle I opted for the truth. I had applied within minutes of registration becoming open and had been fortunate to be granted a spot. He was unimpressed. At this point I realized he had asked the question only as an opener for him to describe his pride at having coerced his way into the course: “well, I told [the organizers] I had already booked the time away from my [insert most esteemed job] and so they had to find room for me.”

What is that adage about those who deserve love the least need it the most?

Better eavesdropping was on offer from an engineer and a young TV producer from Mumbai.

Into the Silence

A bell rang and the cluster shuffled into the dining hall. Once seated, one of the volunteers whose duties had now progressed beyond paperwork pressed ‘play’ on a recording and the group fell quiet. A monotone voice reviewed the ground rules of the course and advised us, again, that unless each of us was committed to observing the full suite of rules for the duration of the course, including remaining within the confines of the mediation centre until 7 am on the morning of the 11th day, we should leave now. The collective response to the directive was silence, awkward shuffling and a few coughs. This was the new norm. We were then allocated our sitting spot in the meditation hall, E-2 for me, and dismissed.

Establishing a routine

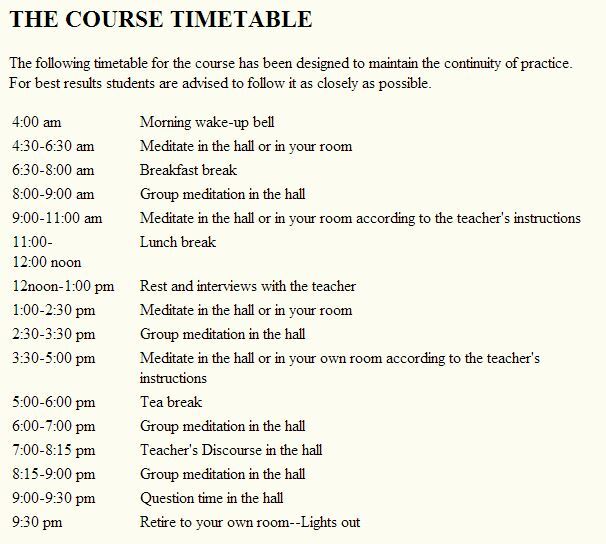

And so began a pattern of excruciatingly early mornings, prolonged periods of seated mental anguish, embattled refrain from overeating at meal times and nightly video lectures delivered by the infamous Vipassana teacher, S.N. Goenka. Although some days are etched in my mind by particular events, there was plenty of routine.

For example, beginning on the first morning, I established a routine of walking (extended pacing?), in between meditation session, along the path that lead from the dining hall to the furthest sleeping quarters. Through this approximation of ‘exercise’, I sought to ensure that I was able to fall asleep come nighttime and that my body wouldn’t become permanently twisted into a lotus pretzel. Later, I came to learn that one fellow participant had nick-named me “Warrior Walker”.

After lunch and walking I would have a short shower. I discovered hot water on the fourth day. As the days progressed, I came to enjoy my cleaning ritual more and more.

By the fifth day, I came to learn that the afternoon meditation session immediately following lunch would be extra challenging if I had gorged myself on the lunch buffet.

The Welders

Although I was now confined to a small space and had volunteered to spend three quarters of my waking hours in mental observation of the tiny section of skin between the bottom of my nostrils and my upper lip, external stimulus continued to exert an outsized influence on my psyche. During the first days, my mind was no quieter than it would be during a normal day. If anything, it was louder. With no phone to distract, no conversation to engage in and few interactions with the world at large, I had more time and space and therefore, greater awareness of my internal monkey mind. It was not enlightening. Probably the opposite. I became annoyed by miniscule things only to, in the absence of distraction, become fixated on how unpleasant it was that I was annoyed. This feeling was compounded by the fact that I knew I was silly to be annoyed. I wanted to be in control of my mind. I wanted to observe calmly and reserve judgement. Why couldn’t I just take a deep breath and move past the feeling of agitation?

A hallmark example was my battle with the welders.

They appeared on the second day. Three local dudes with tools, I gathered, had been hired to string a chain link fence vertically on either side of the walkways which were not already closed in between the furthest sleeping quarters and the dhamma and dining halls. I guess this was deemed necessary because of the monkeys that ran around the compound, hammering on rooftops and swinging between tree branches. Although the monkeys were aggressive with each other, they didn’t appear to threaten any of us (unless you had food) and, in my opinion, further encasing the compound in ugly metal would do far more to detract from the otherwise open and natural forest setting than it would to prevent the monkeys from harming someone.

Anyway, these guys were at work and I allowed them to annoy me. First, they blocked off the stretch of pathway that I walked as part of my routine. I could tell you I wasn’t seeking to be defiant, but I’m not sure how true that was. I admit I felt entitled to walk the path in peace. In my mind, these guys could be doing their work during any of the extended hours that the course go-ers were seated in the Dhamma Hall. It seemed more than coincidental that the end of their tea break coincided with the start of our meditation one. Additionally, they made a mess. The path I would walk after meals was strewn with tools and included an electrical cord used to power a small generator that laid unfurled in extended sections. Finally, they were welding! Not exactly Zen, chaps.

Were it a normal scenario, I would have either struck up a conversation with these guys to understand why they had to be doing the work they were completing at that moment or left the area to complete my walk later. In this scenario, neither was available to me. My only option was to rise above and chose for it not to drag on my mental mindset, and thus my experience. I tried not to hate them. I tried to take deep breaths and not become a prisoner to the endless eddies of being wronged. It took effort.

The Ups and Downs

Although I was sitting in a dim room for most of each day, many memories mark the passage of time. Most of them are odd internal dialogues or esoteric observations that probably, unless the reader has been stimulus-deprived for 7 days straight, won’t be too meaningful. So instead I’ll highlight the arc of the 10 days.

- Day 1 was fine. Everything was new. I was calm and filled with determination.

- Day 3 was the hardest. My body hurt and the 4 am wakeups were beginning to compound. In the Dhamma Hall, short bursts of focus were constantly being pricked by long episodes of exploration into the caverns of my mind.

- By Day 5 I had resolved to give up. This was stupid. Why would anyone sit in silence for 10 hours a day for 10 days?

- On Day 6, things changed. Sort of. My mind now believed that I was ready to leave because I was now confident I would be able to complete the 10 days and so, now that I knew I could do it, there was little additional benefit in actually remaining in the compound for the entire duration. Instead, given that life is short and death could afflict me any day, I might as well escape to re-join my wonderful wife in the land of freedom where I could eat falafels, drink cappuccinos and do yoga at my leisure. How’s that for logic…

- Also on Day 6, the lack of physical contact had caught up with me. The two-hour Zen session following the midday meal saw me struggling to concentrate on moving energy methodically through my body and instead infatuated with the fantasy of running my hands along my wife’s. Noble silence includes forsaking physical pleasure of any kind. Not a good situation.

- Day 7 was positive. Although my dedication to the full two hour sit between 4:30 and 6:30am had slipped, I was having some success with the techniques that had been introduced. Instead of limiting concentration to the flow of our breath on the tip of our upper lip as we had done for the first 5.5 days, we had now been instructed to, beginning with the top of the head, pass awareness methodically over each portion of the body. My sequence would go: top of the head, the forehead, the right eye socket, the left eye socket, the nose, the upper lip, the month, the left cheek, the left ear, the right cheek, the right ear, the chin. Once the face had been energized, I continued south to the neck, arms, chest, abdomen, legs and feet, passing over each defined region with the same methodical intention. Then, the direction reversed, passing back towards my head by along the underside of the feet, backside of the legs and full back and neck. The goal, as I understood it, was to move on from a given area only once your focused awareness had brought a tingling sensation to the space. Aligned with the philosophical teachings that were delivered each evening via video lecture, we wanted to gain familiarity with the principle that things arise and pass away. They aren’t fixed, nor permanent. We weren’t to pass judgement over the sensations we felt (or failed to feel). Simple, intentional observation only.

- Day 8 was a real breakthrough. At best, I was making serious headway at calming my mind and heightening my ability to focus my mind with limited effort. A cynic might say that I had simply run out other things to think about. The truth is likely somewhere in between and, regardless, the outcome was very positive.

- Day 9, now spurred by the approaching end to the ten days of torture, was also positive. Throughout the week, it was generally not frowned upon to exit the Dhamma Hall, during a meditation session, in order to regain focus or move your body or for any other reason. Additionally, if you chose to change sitting positions, no problem. Beginning on Day 7 however the teacher introduced Strong Determination sits where the objective was to, for an entire hour at a time, move as little as possible and ideally not at all. On Day 9 I completed two 1-hour sessions in which I was inert (or probably just more physically still than I had ever imagined I could be). These also happened to be among my best sitting sessions. It was a good day.

- Day 10 – by mid-morning we broke noble silence. We were to remain in the compound until the next morning and still attend meditation sessions, however we were now permitted to speak to others. I had mixed feelings about the conclusion of our silence not coinciding with our release from the compound. So much so that I attempted to escape…

What Did It All Mean?

Honestly, I’m not completely sure. In its most simple terms, it was an experience, and probably the most challenging one I have so far endured at that. I certainly feel richer for it. That said, have I maintained a meditation practice since? No. Do I think the world would be a different place if everyone tried a ten-day retreat? Probably. Would I recommend to others? Yes. If you apply to attend, just watch out for the welders.